Data or it didn't happen

Today, there is incredible excitement, enthusiasm and euphoria about technology trends such as Wearables, Big Data and the Internet of Things. Listening to some speakers at conferences, it often sounds like the convergence of these technologies promises to solve every problem that humanity faces. Seemingly, all we need to do is let these new ideas, products and services emerge into society, and it will be happy ever after. Just like those fairy tales we read to our children. Except, life isn't a fairy tale, neither is it always fair and equal. In this post, I examine how these technologies are increasingly of interest to employers and insurers when it comes to determining risk, and how this may impact our future.

Let's take the job interview. There may be some tests the candidate undertakes, but a large part of the interview is the human interaction, and what the interviewer(s) and interviewee think of each other. Someone may perform well during the interview, but turn out to under perform when doing the actual job. Naturally, that's a risk that every employer wishes to minimise. What if you could minimise risk with wearables during the recruitment process? That's the message of a recent post on a UK recruitment website, "Recruiters can provide candidates with wearable devices and undertake mock interviews or competency tests. The data from the device can then be analysed to reveal how the candidate copes under pressure." I imagine there would be legal issues if an employer terminated the recruitment process simply on the basis of data collected from a wearable device, but it may augment the existing testing that takes place. Imagine the job is a management role requiring frequent resolution of conflicts, and your verbal answers convince the interviewer you'd cope with that level of stress. What if the biometric data captured from the wearable sensor during your interview showed that you wouldn't be able to cope with that level of stress. We might immediately think of this as intrusive and discriminatory, but would this insight actually be a good thing for both parties? I expect all of us at one point have worked alongside colleagues who couldn't handle pressure, and their reactions caused significant disruption in the workplace. Could this use of data from wearables and other sensors lead to healthier and happier workplaces?

Could those recruiting for a job start even earlier? What if the job involved a large amount of walking, and there was a way to get access to the last 6 months of activity data from the activity tracker you've been wearing on your wrist every day? Is sharing your health & fitness data with your potential employer the way that some candidates will get an edge over other candidates that haven't collected that data? That assumes that you have a choice in whether you share or don't share, but what if every job application required that data by default? How would that make you feel?

Will the online job application of the future also request access to the health & fitness data from your #wearables? #privacy

— Maneesh Juneja (@ManeeshJuneja) June 26, 2015What if it's your first job in life, and your employer wants access to data about your performance during your many years of education? Education technology used at school which aims to help students may collect data that could tag you for life as giving up easily when faced with difficult tasks. The world isn't as equal as we'd like it to be, and left unchecked, these new technologies may worsen inequalities, as Cathy O’Neil highlights in a thought provoking post on student privacy, “The belief that data can solve problems that are our deepest problems, like inequality and access, is wrong. Whose kids have been exposed by their data is absolutely a question of class.”

There is increasing interest in developing wearables and other devices for babies, tracking aspects of a baby, mainly to provide additional reassurance to the parents. In theory, maybe it's a brilliant idea, with no apparent downsides? Laura June doesn't think so, She states, "The merger of the Internet of Things with baby gear — or the Internet of Babies — is not a positive development." Her argument against putting sensors into baby gear is that it would increase anxiety levels in parents, not reduce them. I'm already thinking about that data gathered from the moment the baby is born. Who would own and control it? The baby, the baby's parents, the government or the corporation that had made the software & hardware used to collect the data? Furthermore, what if the data from the baby could impact not just access to health insurance, but the pricing of the premium paid by the parents to cover the baby in their policy? Do you decide you don't want to buy these devices to monitor the health of your newborn baby in case one day that data might be used against your child when they are grown up?

When we take out health and life insurance, we fill in a bunch of forms, supply the information needed for the insurer to determine risk, and then calculate a premium. Rick Huckstep points out, "The insurer is not able to reassess the changing risk profile over the term of the policy." So, you might be active, healthy and fit when you take out the policy, but what if your behaviour changes and your risk profile changes during the term of the policy? This is the opportunity that some are seeing for insurers to use data from wearables to determine how your risk profile changes during the term of the policy. Instead of a static premium at the outset, we have a world with dynamic and personalised premiums. Huckstep also writes, "Where premiums will adjust over the term of the policy to reflect a policyholder’s efforts to reduce the risk of ill-health or a chronic illness on an on-going basis. To do that requires a seismic shift in the approach to underwriting risk and represents one of the biggest areas for disruption in the insurance industry."

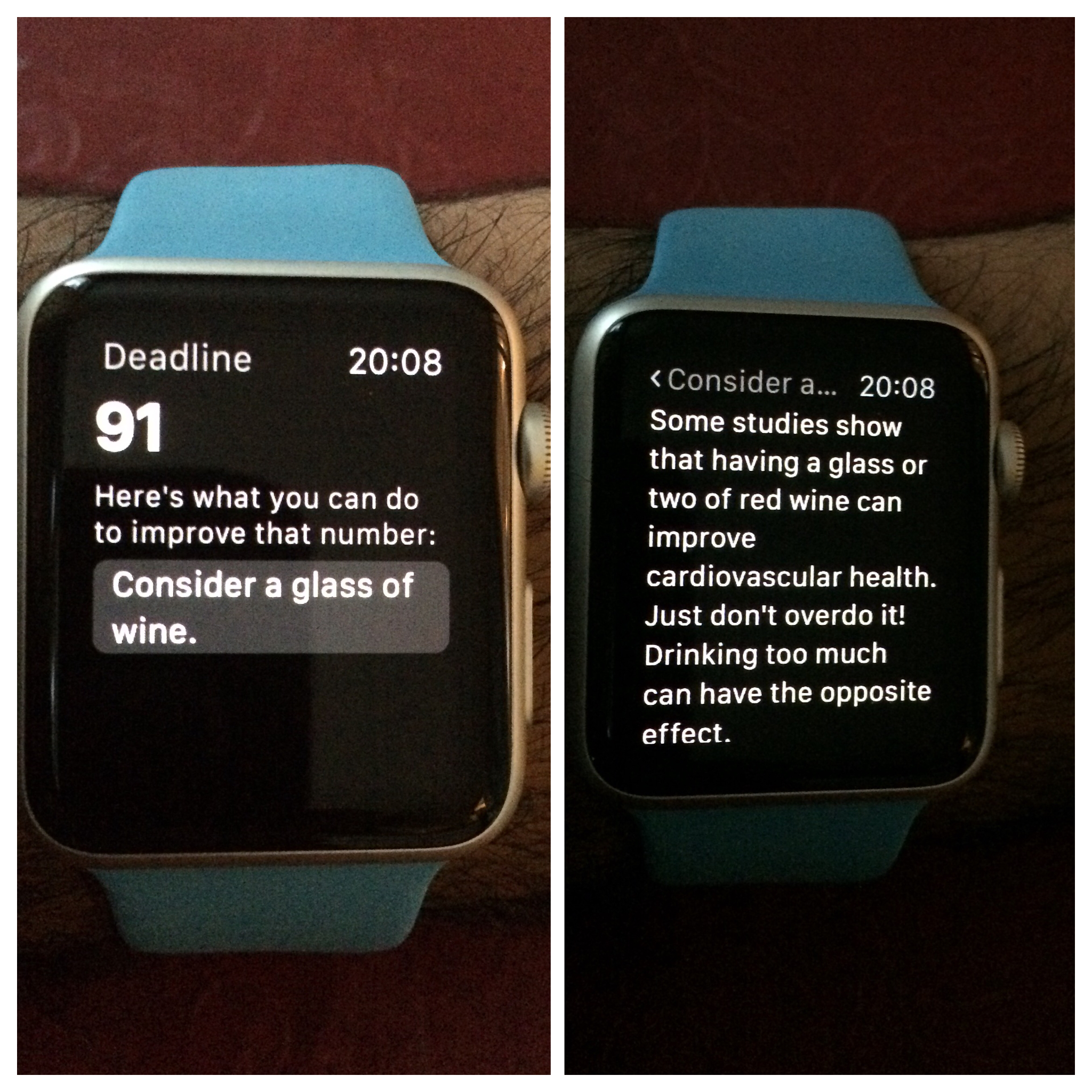

Already today, you can link your phone or wearable to Vitality UK health insurance, and accumulate points based upon your activity (e.g. 10 points if you walk 12,500+ steps in a day). Get enough points and exchange them for rewards such as a cinema ticket. A similar scheme has also launched in the USA with John Hancock for life insurance.

Is Huckstep the only one thinking about a radically different future? Not at all. Neil Sprackling, Managing Director of Swiss Re (a reinsurer) has said, “This has the potential to be a mini revolution when it comes to the way we underwrite for life insurance risk." In fact, his colleague, Oliver Werneyer, has an even bolder vision with a post entitled, "No wearable device = no life insurance," in which he believes that in 5 to 10 years time, you might find not be able to buy life insurance if you don't have a wearable device collecting data about you and your behaviour. Direct Line, a UK insurer believe that technology is going to transform insurance. Their Group Marketing Director, Mark Evans, has recently talked about technology allowing them to understand a customer's "inherent risk." Could we be penalised for deviating away from our normal healthy lifestyle because of life's unexpected demands? In this new world, if you were under chronic stress because you suddenly had to take time off work to look after a grandparent that was really sick, would less sleep and less exercise result in a higher premium next month on your health insurance? I'm not sure how these new business models would work in practice.

When it comes to risk being calculated more accurately based upon this stream of data from your wearables, surely it's a win-win for everyone involved? The insurers can calculate risk more accurately, and you can benefit from a lower premium if you take steps to lower your risk. Then there are opportunities for entrepreneurs to create software & hardware that serves these capabilities. Would the traditional financial capitals such as London and New York be the centre of these innovations?

One of the big challenges to overcome, above and beyond established data privacy concerns, is data accuracy. In my opinion, these consumer devices that measure your sleep & steps are not yet accurate and reliable enough to be used as a basis for determining your risk, and your insurance premium. Sensor technology will evolve, so maybe one day, there will be 'insurance grade' wearables that your insurer will be able to offer you. These would be certified to be accurate, reliable and secure enough to be used in the context of being linked to your insurance policy. In this potential future, another issue is whether people will choose to not take insurance because they don't want to wear a wearable, or they simply don't like the idea of their behaviour being tracked 24/7. Does that create a whole new class of uninsured people in society? Or would their be so much of a backlash from consumers (or even policy makers) to this idea of insurers accessing this 24/7 stream of data about your health, that this new business model never becomes a reality? If it did become a reality, would consumers switch to those insurers that could handle the data from their wearables?

Interestingly, who would be an insurer of the future? Will it be the incumbents, or will it be hardware startups that build insurance businesses around connected devices? That's the plan of Beam Technologies, who developed a connected toothbrush (yes, it connects via Bluetooth with your smartphone and the app collects data about your brushing habits). Their dental insurance plan is rolling out in the USA shortly. Beam are considering adding incentives, such as rewards for brushing twice a day. Another experiment is NEST partnering with American Family Insurance. They supply you a 'smart' smoke detector for your home, which "shares data about whether the smoke detectors are on, working and if the home’s Wi-Fi is on." In exchange, you get 5% discount off your home insurance.

Switching back to work, employers are increasingly interested in the data from employee's wearables. Why? Again, it's about a more accurate risk profile when it comes to health & safety of employees. Take the tragic crash of the Germanwings flight this year, where it emerges the pilot deliberately crashed the plane, killing 150 passengers. At a recent event in Australia, it was suggested this accident might have been avoided if the airline were able to monitor stress in the pilot using data from a wearable device.

What other accidents in the workplace might be avoided if employers could monitor the health, fitness & wellbeing of employees 24 hours a day? In the future, would a hospital send a surgeon home because the data from the surgeon's wearable showed they had not slept enough in the last 5 days? What about bus, taxi or truck drivers that could be monitored remotely for drowsiness by using wearables? Those are some of the use cases that Fujitsu are exploring in Japan with their research. Conversely, what if you had been put forward for promotion to a management role, and a year's worth of data from your wearable worn during work showed your employer that you got severely stressed in meetings where you had to manage conflict? Would your employer be justified in not promoting you, citing the data that suggested promoting you would increase your risk of a heart attack? Bosses may be interested in accessing the data from your wearables just to verify what you are telling them. Some employees phone in pretending to be sick, to get an extra day off. In the future, that may not be possible if your boss can check the data from your wearable to verify that you haven't taken many steps as you're stuck in bed at home. If you can't trust your employees to tell the truth, do you just modify the corporate wellness scheme with mandatory monitoring using wearable technology?

If it's possible for employers to understand the risk profile for each employee, would those under pressure to increase profits, ever use the data from wearables to understand which employees are going to be 'expensive', and find a way to get them out of the company? Puts a whole new spin on 'People Analytics' and 'Optimising the workforce'. In a compelling post, Sarah O'Connor shares her experiment where she put on some wearables and shared the data with her boss. She was asked how it felt to share the data with her boss, "It felt very weird, and actually, I really didn't like the feeling at all. It just felt as if my job was suddenly leaking into every area of my life. Like on the Thursday night, a good friend and colleague had a 30th birthday party, and I went along. And it got to sort of 1 o'clock, and I realized I was panicking about my sleep monitor and what it was going to look like the next day." We already complain about checking work emails at home, and the boundaries between work and home blurring. Do you really want to be thinking about how skipping your regular session at the gym on a Monday night would look to your boss? Devices that will betray us can actually be a good thing for society. Take the recent case of a woman in the USA who reported being sexually assaulted whilst she was asleep in her own home at night. The police used the data from the activity tracker she wore on her wrist to prove that at the time of the alleged attack, she was not asleep but awake and walking. On the other hand, one might also consider that those with malicious intent could hack into these devices and falsify the data to frame you for a crime you didn't commit.

If these trends continue to converge, I see enterprising criminals rubbing their hands with glee. A whole new economy dedicated to falsifying the stream of data from your wearable/IoT device to your school, doctor, insurer or employer, or whoever is going to be making decisions based upon that stream of data. Imagine it's the year 2020, you are out partying every night, and you pay a hacker to make it appear that you slept 8 hours a night. So many organisations are blindly jumping into data driven systems with the mindset of, 'In data, we trust,' that few bother to think hard enough about the harsh realities of real world data. Another aspect is bias in algorithms using this data about us. Hans de Zwart has written an illuminating post, "Demystifying the algorithm: Who designs our life?" Zwart shows us the sheer amount of human effort in designing Google Maps, and the routes it generates for us, "The incredible amount of human effort that has gone into Google Maps, every design decision, is completely mystified by a sleek and clean interface that we assume to be neutral. When these internet services don’t deliver what we want from them, we usually blame ourselves or “the computer”. Very rarely do we blame the people who made the software." With all these potential new algorithms classifying our risk profile based upon data we generate 24/7, I wonder how much transparency, governance and accountability there will be?

There is much to think about and consider, one of the key points is the critical need for consumers to be rights aware. An inspiring example of this, is Nicole Wong, the former US Deputy CTO, who wrote a post explaining why she makes her kids read privacy policies. One sentence in particular stood out to me, " When I ask my kids about what data is collected and who can access it, I am asking them to think about what is valuable and what they are prepared to share or lose." Understanding the value exchange that takes place when you share your data with a provider is critical step towards being able to make informed choices. That's assuming all of us have a choice in the sharing of our data. In the future, when we teach our children how to read and write English, should they be learning 'A' is for algorithm, rather than 'A' is for apple? I gave a talk in London recently on the future of wearables, and I included a slide on when wearables will take off (slide 21 below). I believe they will take off when we have to wear them or when we can't access services without them. Surgeons and pilots are just two of the professions which may have to get used to being tracked 24/7.

Will the mantra of employers and insurers in the 21st century be, "Data or it didn't happen?"

If Big Data is set to become one of the greatest sources of power in the 21st century, that power needs a system of checks and balances. Just how much data are we prepared to give up in exchange for a job? Will insurance really be disrupted or will data privacy regulations prevent that from happening? Do we really want sensors on us, in our cars, our homes & our workplaces monitoring everything we do or don't do? Having data from cradle to grave on each of us is what medical researchers dream of, and may lead to giant leaps in medicine and global health. UNICEF's Wearables for Good challenge could solve everyday problems for those living in resource poor environments. Now, just because we might have the technology to classify risk on a real time basis, do we need to do that for everyone, all the time? Or should policy makers just ban this methodology before anyone can implement it? Is there a middle path? "Let's add in ethics to technology" argues Jennifer Barr, one of my friends who lives and works in Silicon Valley. Instead of just teaching our children to code, let's teach them how to code with ethics.

There are so many questions, and still too few places where we can debate these questions. That needs to change. I am speaking at two events in London this week where these questions are being debated, the Critical Wearables Research Lab and Camp Alphaville. I look forward to continuing the conversation with you in person if you're at either of these events.

[Disclosure: I have no commercial ties to any of the individuals or organisations mentioned in the post]