How do we measure health?

I saw a tweet which made me really think about our existing approaches to measuring our health.

Why don't doctors ever ask patients what "healthy" means to them? I measure it by whether I'm able to ride my horse. What about you? #hcldr

— Morgan Gleason (@morgan_gleason) August 12, 2014Morgan Gleason is a 15 year old girl who lives in the USA. She was diagnosed with a rare disease, Juvenile Dermatomyositis (JDM) at the age of 11. From her website, "The main symptoms of JDM are weak or painful muscles, skin rash, fatigue and fever." I wonder how many other Morgans are out there? How many feel that their voice as a patient needs to be heard?

I speak to patients regularly as part of my research in Digital Health, and many of them tell me when they visit their doctor, what they want is health. Not Health IT, Digital Health, Health Outcomes, but plain and simple Health. There is too often a tendency for those in health & social care, in whatever function, to prioritise on what makes their lives easier, what makes the system more efficient or even what allows them to increase profitability.

We're hearing more and more talk about data driven health. For the last decade, I've worked with epidemiologists and health economists in the pharmaceutical industry to use patient data the USA, UK, France & Germany to help decision makers understand how drugs are used in the real world. My work has contributed to speeding up drug development and helping to make drugs safer. So, what kind of data on patients? Typically, data from 'real world settings', i.e. the doctor's office or the hospital. One of the most common types of research projects I've worked on, has been to use these databases to help researchers understand the natural history of a particular disease. For example, when I look at the data, I can answer questions such as;

When were patients diagnosed?

What the patients were diagnosed with?

Were the patients treated after diagnosis?

If so, what kind of drug?

Were lab tests ordered?

If so, what were the results?

When patients were hospitalised?

How long the patients were hospitalised for?

What's frustrating for me and others is that the existing data collected from doctor's offices and hospitals doesn't show the full picture of a patient's health. If I have to look at medication adherence, and if the database shows that some patients don't have a repeat prescription for their medication when they're supposed to, why is that?

The transactional data currently available from healthcare systems doesn't tell me WHY. With 'Big Data' being frequently part of conversations about innovation in health & social care, collecting even more of the same type of data doesn't seem logical. There are major gaps in existing 'Big Data', and for me, that's patient generated health data (PGHD). It's the marriage of 'hard' data from the system and 'soft' data from the patients that could be the key to meeting the challenges ahead of us.

How do individuals measure their health?

What value might be unlocked if we understood how different people measure their health? The system might currently measure someone's health based upon clinically validated instruments, i.e. blood pressure, blood glucose, cholesterol, and so forth, but how do people measure their own health? More importantly, how can the system accommodate data such as whether Morgan is able to ride her horse or not?

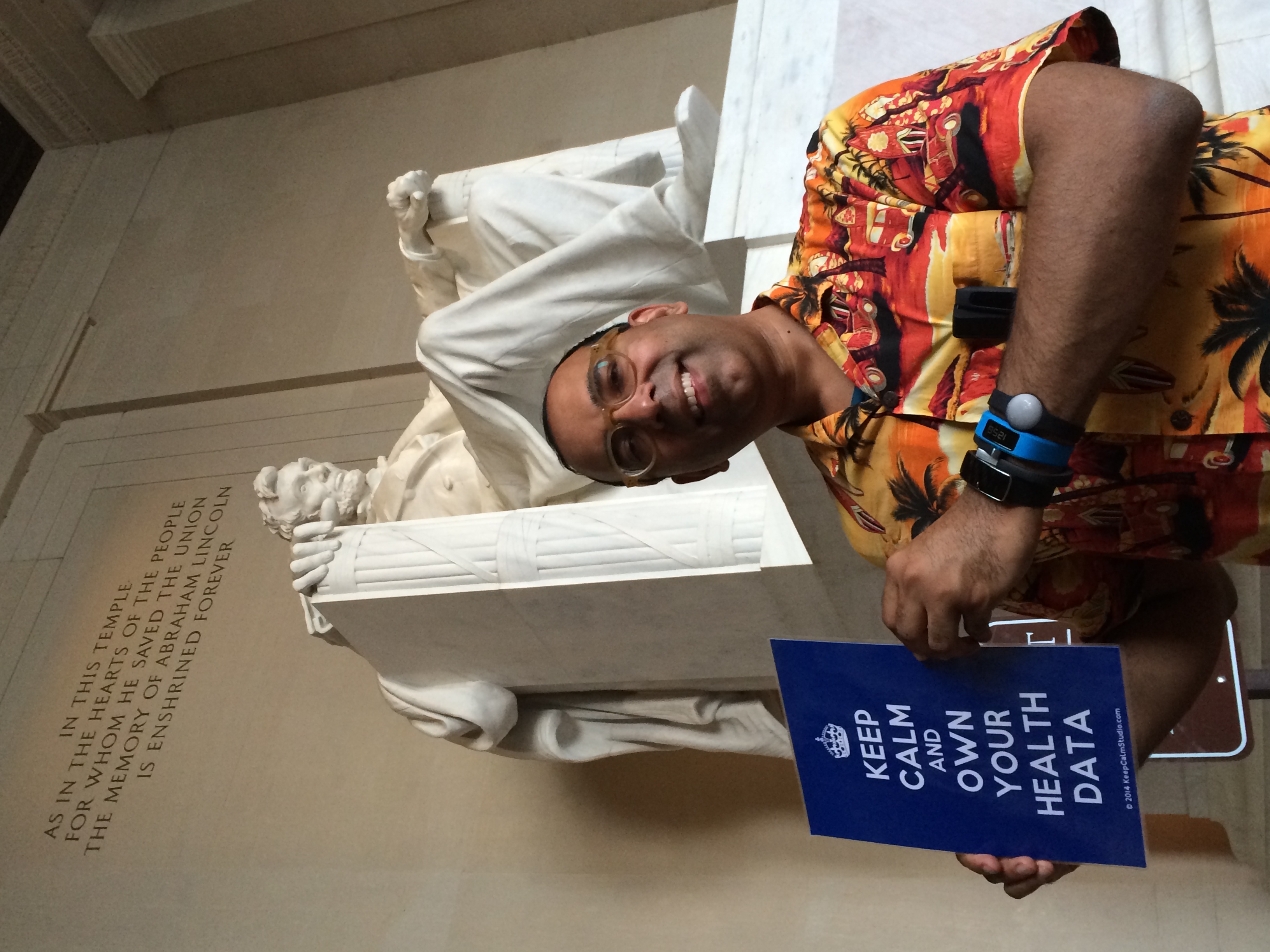

More and more people have been using activity trackers such as Fitbit to track how active they are, and even using the social elements of the app to compete with their friends and family. Some are even sharing the data & insights gained from their Fitbits with their doctors. For many medical professionals, the data from consumer devices such as Fitbit has limited or no clinical value, even if they had systems which could incorporate such data into the patient's record. The array of hardware and software increasingly becoming available to consumers to monitor aspects of their health is largely unproven. So what to do?

It's fascinating to read about Dr Josh Umbehr, a doctor in the USA who not only welcomes patient generated data from devices such as Fitbits, but has built his own computer system in his practice which can accept data from a patient's Fitbit. “We don’t know what all this data means, yet,” Umbehr said, “but I can discuss it with the patients and we can both follow it.”

I have much sympathy for over worked doctors who are apprehensive about dealing with these new streams of data. Whilst patients collecting all sorts of (unvalidated) data about themselves sounds great in theory, it could be dangerous if used and interpreted in isolation. I even ran a Health 2.0 London event in 2013 entitled, "Information Obesity: A possible side effect of Digital Health?" Having to deal with patient generated health data could even put physicians at risk, as Sue Montgomery points out, "providers could be held liable if they don’t review all information in the patient’s record—if this lack of review leads to misdiagnosis or other patient harm."

However, do patients wishing to share data from their Fitbit signify the emergence of a new era where patients can themselves choose to capture (and share) data that is important to them? Thinking back to the patient databases I work with, if I observe that a patient doesn't visit the doctor for 6 months, does that mean during those 6 months they were healthy, they were well?

What new discoveries might happen if patients were able to bring data into the system that measured health based upon their own experience? Would that future involve having to reboot Health IT infrastructure as we know it? There is already the pioneering personal health record system called Patients Know Best developed in the UK, which in March 2014 had the ability to integrate data from 100 devices and apps.

However, should we limit patient generated data to structured data like number of steps or number of hours slept? In a thought provoking post about patient generated health data, Dr Scott Nelson says, "Unstructured data gathering tools like Apple’s Siri could be used to capture and store patient verbal input and feedback on regular basis. This unstructured data could be parsed into structured formats that could then be automatically organized, analyzed, and visualized for doctor’s use at the time of care."

If patients like Morgan were able to use Siri to measure their health simply by speaking into the phone, why aren't we offering that to patients today? Would you feel comfortable sharing how healthy you are feeling by speaking into your phone? Who is thinking about the patient data in the form of digital diaries, video, audio, pictures? Are we heading towards a world where the data on your smartphone will reveal more about your health than the data collected during your visits to the doctor?

Understanding human health

If medicine revolves around disease, what if we could measure and maximise wellness? Dr Lee Hood in the USA aims to see if we could with his 100K Wellness Project. It's an ambitious study that aims to enroll 100,000 people over the next 20 years (subject to funding). What I find fascinating is that Dr Hood wants to quantify "wellness".

Do we have to reboot the entire system of medicine to truly understand human health? New research suggests people with friendly neighbours and strong community ties are less likely to suffer heart attacks. When was the last time your doctor asked you how friendly your neighbours are? When was the last time your doctor asked you if you feel like you belong to a community? Even if they did ask you these questions, where on the paper form do they record such information?

Where have you lived? In Bill Davenhall's TEDMED talk in 2009, he shows how where have lived can impact our health. Yet, our place history is not in our medical records. Now, an electronic health record (EHR) is defined as a systematic collection of electronic health information about an individual patient or population. Ironically, when EHRs are being developed, how many stop to ask patients how THEY measure their health?

It's encouraging to read of a system that is building technology today which allows us to understand what's important to a patient. For example, the Hudson Center for Health Equity & Quality have developed a "system that captures patient data on who the patient actually is, what is important to the them and what’s preventing the patient from getting the necessary care." We need more institutions to take these bold leaps forward.

The future

Whilst it's clear that health & social care systems are being stretched beyond their limits, what's not clear is how we prepare our people, policies & processes to be able to cope with an increasingly complex and uncertain future. Just because we've measured our health in a certain way up till now, do we keep doing the same in future years? Can we really accommodate the needs of all stakeholders? Who will be the winners and losers in this new era? Technology is merely the tool here, and probably the simplest factor in the equation. Ultimately, it's the combination of people, policies and processes moving in tandem that will trigger the change many of us are hoping will occur.

Moving forward won't be simple or easy. Yes, change is typically tough to navigate and often downright terrifying. However, the inspiring Sir Ken Robinson reminds us that "imagination is the source of all human achievement". Yet, the most dangerous words I keep hearing from decision makers in health & social care are "We've always done it this way". Is your organisation tapping into the imagination of your employees?

I'm curious to know what health means to YOU, and how YOU measure your own health? Feel free to leave a comment below, reply to me via Twitter or email.

[Disclosure: I have no commercial ties with the individuals and organisations mentioned in this post]