You can't care for patients, you're not human!

We're are facing a new dawn, as machines get smarter. Recent advancements in technology available to the average consumer with a smartphone are challenging many of us. Our beliefs, our norms and our assumptions about what is possible, correct and right are increasingly being tested. One area where I've been personally noticing very rapid developments is in the arena of chatbots, software available to us on our phones and other devices that you can have a conversation with using natural language and get tailored replies back, relevant to you and your particular needs at that moment. Frequently, the chatbot has very limited functionality, and so it's just used for basic customer service queries or for some light hearted fun, but we are also seeing the emergence of many new tools in healthcare, direct to consumers. One example are 'symptom checkers' that you could consult instead of telephoning a human being or visiting a healthcare facility (and being attended to by a human being), and another example are 'chatbots for mental health' where some some form of therapy is offered and/or mood tracking capabilities are provided.

It's fascinating to see the conversation about chatbots in healthcare being one of two extreme positions. Either we have people boldly proclaiming that chatbots will transform mental health (without mentioning any risks) or others (often healthcare professionals and their patients) insisting that the human touch is vital and no matter how smart machines get, humans should always be involved in every aspect of healthcare since machines can't "do" empathy. Whilst I've met many people in the UK who have told me how kind, compassionate and caring the staff have been in the National Health Service (NHS) when they have needed care, I've not had the same experience when using the NHS throughout my life. Some interactions have been great, but many were devoid of the empathy and compassion that so many other people receive. Some staff behaved in a manner which left me feeling like I was a burden simply because I asked an extra question about how to take a medication correctly. If I'm a patient seeking reassurance, the last thing I need is be looked at and spoken to like I'm an inconvenience in the middle of your day.

MY STORY

In this post, I want to share my story about getting sick, and explain why that experience has challenged my own views about the role of machines and humans in healthcare. So we have a telephone service in the UK from the NHS, called 111. According to the website, "You should use the NHS 111 service if you urgently need medical help or advice but it's not a life-threatening situation." The first part of the story relates to my mother, who was unwell for a number of days and not improving, and given her age and long term conditions was getting concerned, one night she chose to dial 111 to find out what she should do.

My mother told me that the person who took the call and asked her a series of questions about her and her symptoms seemed to rush through the entire call and through the questions. I've heard the same from others, that the operators seem to want to finish the call as quickly as possible. Whether we are young or old, when we have been unwell for a few days, and need to remember or confirm things, we often can't respond immediately and need time to think. This particular experience didn't come across as a compassionate one for my mother. At the end of the call, the NHS person said that a doctor would call back within the hour and let her know what action to take. The doctor called and the advice given was that self care at home with a specific over the counter medication would help her return to normal. So she got the advice she needed, but the experience as a patient wasn't a great one.

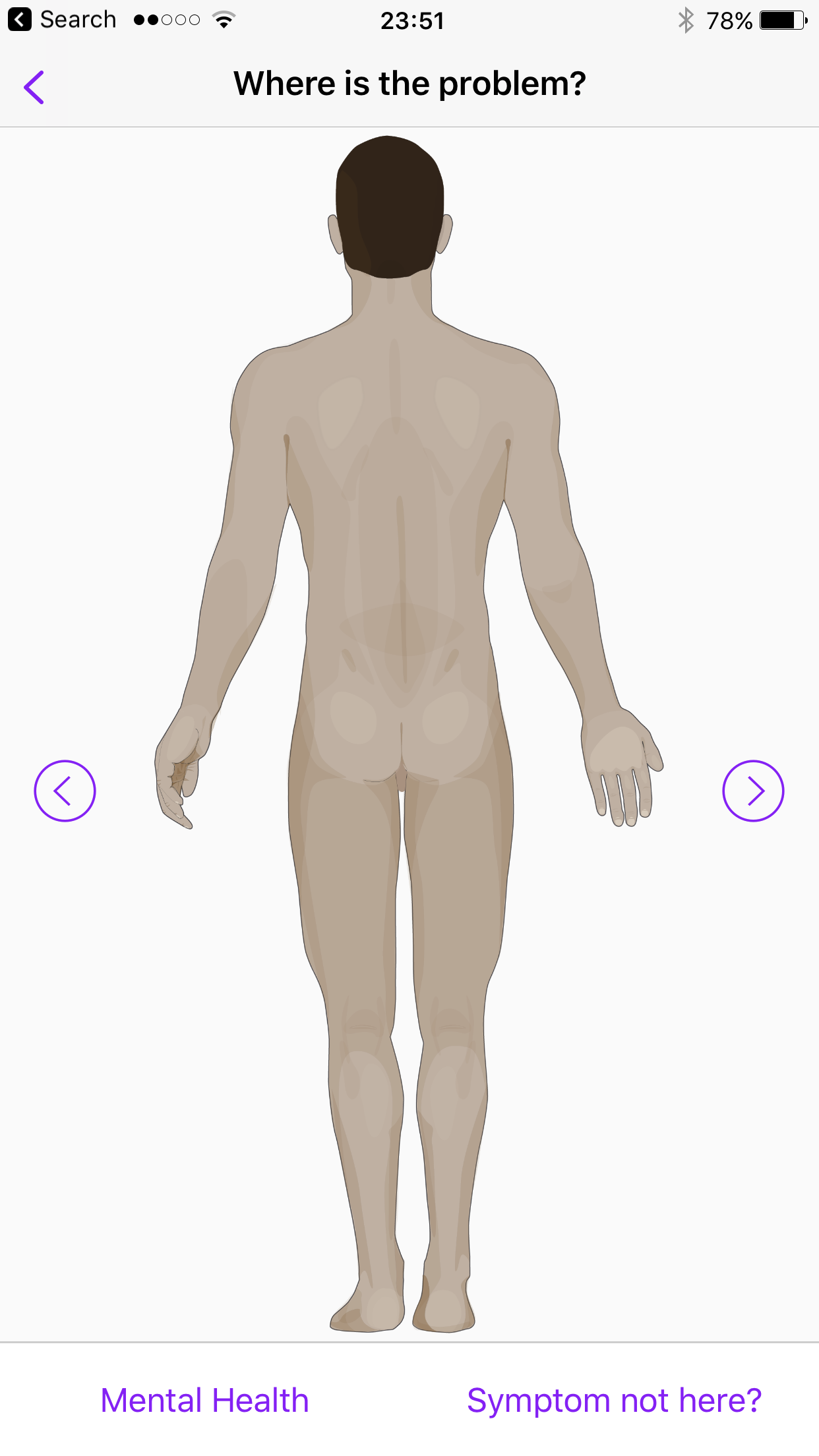

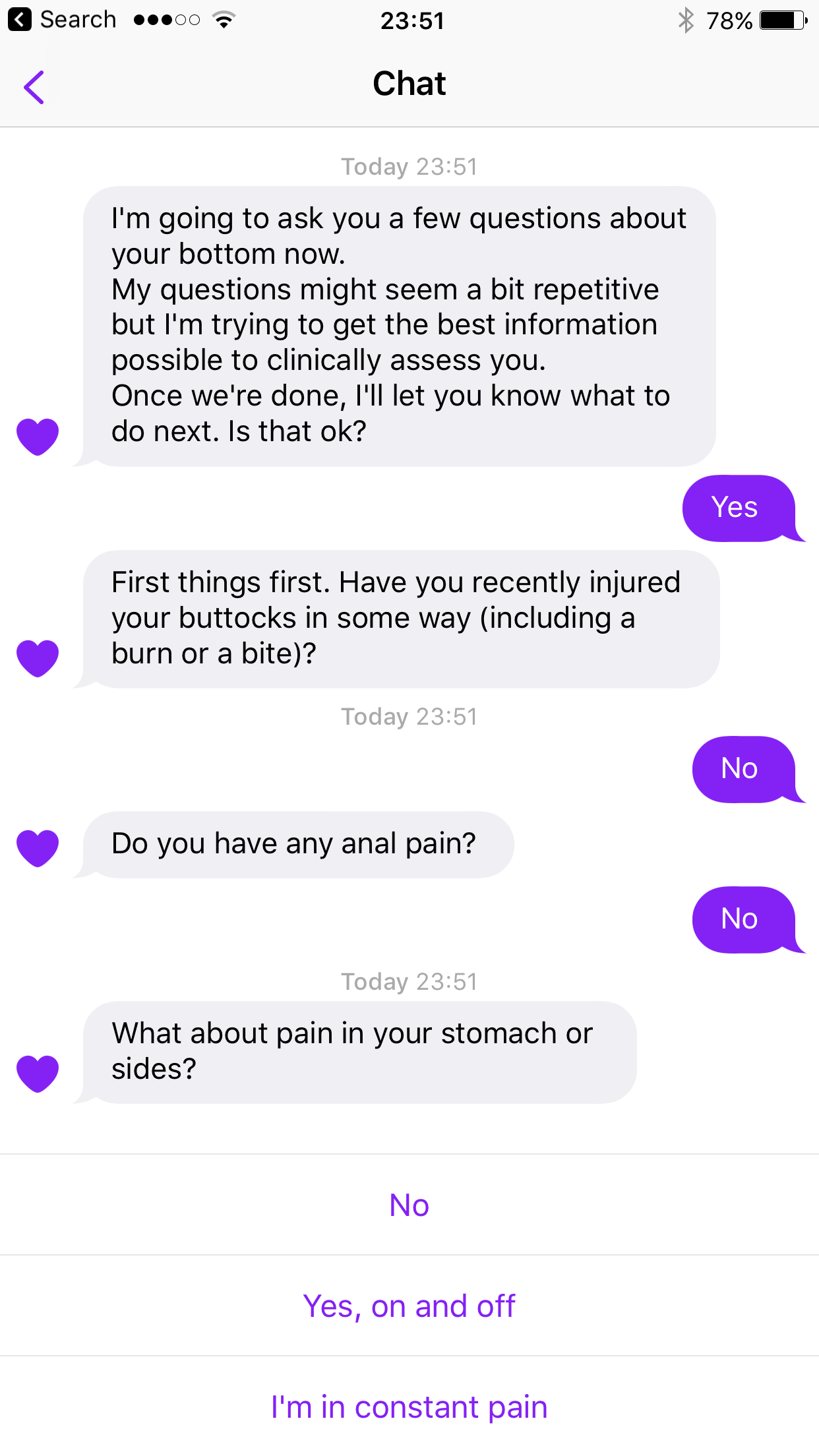

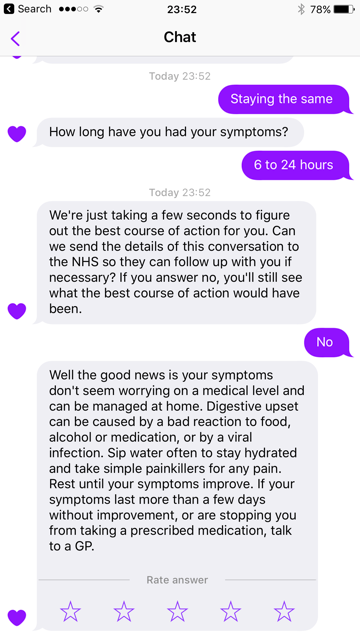

Now a few weeks later, I was also unwell, it wasn't life threatening, the local urgent care centre was closed, and given my mother's experience with 111 over the telephone, I decided to try the 111 app. Interesingly, the app is powered by Babylon, which is one of the most well known symptom checker apps. Given that the NHS put their logo on the app, I felt reassured, as it made me feel that it must be accurate, and must have been validated. Without having to wait for a human being to pick up my call, I got the advice I needed (which again was self care) and most importantly I had time to think when answering. The process of answering the questions that the app asked was under my control. I could go as fast or as slowly as I wanted, the app wasn't trying to rush me through the questions. On this occasion, and when contrasting with my mother's experience of the same service but with a human being on the end of the telephone were very different. It was a very pleasant experience, and the entire process was faster too, as in my particular situation, I didn't have to wait for a doctor to call me back after I'd answered the questions. The app and the Artificial Intelligence (AI) that powers Babylon was not necessarily empathetic or compassionate like a human that cares would be, but the experience of receiving care from a machine was an interesting one. It's just two experiences in the same family of the same healthcare system, accessed through different channels. Would I use the app or the telephone next time? Probably the app. I've now established a relationship with a machine. I can't believe I just wrote that.

I didn't take screenshots of the app during the time that I used it, but I went back a few days later and replicated my symptoms and here are a few of the screenshots to give you an idea of my experience when I was unwell.

It's not proof that the app would work every time or for everyone, it's simply my story. I talk to a lot of healthcare professionals, and I can fully understand why they want a world where patients are being seen by humans that care. It's quite a natural desire. Unfortunately, we have a shortage of healthcare professionals and as I've mentioned not all of those currently employed behave in the desired manner.

The state of affairs

The statistics on the global shortage make for shocking reading. A WHO report from 2013 cited a shortage of 7.2 million healthcare workers at that time, projected to rise to 12.9 million by 2035. Planning for future needs can be complex, challenging and costly. The NHS is looking to recruit up to 3,000 GPs from outside of the UK. Yet 9 years ago, the British Medical Association voted to limit the number of medical students and to have a complete ban on opening new medical schools. It appears they wanted to avoid “overproduction of doctors with limited career opportunities.” Even the sole superpower, the USA is having to deal with a shortage of trained staff. According to recent research, the USA is facing a shortage of between 40,800 and 104,900 physicians by 2030.

If we look at mental health specifically, I was shocked to read the findings of a report that stated, "Americans in nearly 60 percent of all U.S. counties face the grim reality that they live in a county without a single psychiatrist." India, with a population of 1.3 billion has just 3 psychiatrists per million people. India is forecasted to have another 300 million people by 2050. The scale of the challenge ahead in delivering care to 1.6 billion people at that point in time is immense.

So the solution seems to be just about training more doctors, nurses and healthcare workers? It might not be affordable, and even if it is, the change can take up to a decade to have an impact, so doesn't help us today. Or maybe we can import them from other countries? However, this only increases the 'brain drain' of healthcare workers. Or maybe we work out how to shift all our resources into preventing disease, which sounds great when you hear this rallying cry at conferences, but again, it's not something we can do overnight. One thing is clear to me, that doing the same thing we've done till now isn't going to address our needs in this century. We need to think differently, we desperately need new models of care.

New models of care

So I'm increasingly curious as to how machines might play a role in new models of care? Can we ever feel comfortable sharing mental health symptoms with a machine? Can a machine help us manage our health without needing to see a human healthcare worker? Can machines help us provide care in parts of the world where today no healthcare workers are available? Can we retain the humanity in healthcare if in addition to the patient-doctor relationship, we also have patient-machine relationships? I want to show a couple of examples where I have tested technology which gives us a glimpse into the future, with an emphasis on mental health.

Google's Assistant that you can access via your phone or even using a Google Home device hasn't necessarily been designed for mental health purposes, but it might still be used by someone in distress who turns to a machine for support and guidance. How would the assistant respond in that scenario? My testing revealed a frightening response when conversing with the assistant (It appears Google have now fixed this after I reported it to them) - it's a reminder that we have to be really careful how these new tools are positioned so as to minimise risk of harm.

We keep hearing so much about #AI transforming healthcare, yet look at this. I'm flabbergasted. #digitalhealth pic.twitter.com/xtyDFY3z2s

— Maneesh Juneja (@ManeeshJuneja) October 22, 2017

I also tried Wysa, developed in India and described on the website as a "Compassionate AI chatbot for behavioral health." It uses Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to support the user. In my real world testing, I found it to be surprisingly good in terms of how it appeared to care for me through it's use of language. Imagine a teenage girl, living in a small town, working in the family business, far away from the nearest clinic, and unable to take a day off to visit a doctor. However, she has a smartphone, a data plan and Wysa. In this instance, surely this is a welcome addition in the drive to ensure everyone has access to care?

I'm impressed at how Wysa spotted (and responded accordingly) to my cry for help when I submitted some simulated answers #digitalhealth pic.twitter.com/czS8kytx35

— Maneesh Juneja (@ManeeshJuneja) August 5, 2017

Another product I was impressed with was Replika, described on the website as "Replika is an AI friend that is always there for you." The co-founder, Eugenia Kuyda when interviewed about Replike said, “If you feel sad, it will comfort you, if you feel happy, it will celebrate with you. It will remember how you’re feeling, it will follow up on that and ask you what’s going on with your friends and family.” Maybe we need these tools partly because we are living increasingly disconnected lives, disconnected from ourselves and from the rest of society? What's interesting is that the more someone uses a tool like Wysa or Replika over time, the more it learns about you and should be able to provide more useful responses to you. Just like a human healthcare worker, right? We have a whole generation of children growing up now who are having conversations with machines from a very early age (e.g Amazon Echo, Google Home etc) and when they access healthcare services during their lifetime, will they feel that it's perfectly normal to see a machine as a friend and as a capable as their human doctor/therapist?

It did the right thing when I provided simulated answers pretending to be a new user in a state of distress #digitalhealth #AI #nhs pic.twitter.com/7j7DJguvmi

— Maneesh Juneja (@ManeeshJuneja) November 4, 2017

I have to admit that neither Wysa nor MyReplika is perfect, but no human is perfect either. Just look at the current state of affairs where medical error is the 3rd leading cause of death in the USA. Professor Martin Makary who led research into medical errors said, "It boils down to people dying from the care that they receive rather than the disease for which they are seeking care." Before we dismiss the value of machines in healthcare, we need to acknowledge our collective failings. We also need to fully evaluate products like Wysa and Replika. Not just from a clinical perspective, but also from a social, cultural and ethical perspective. Will care by a machine be the default choice unless you are wealthy enough to be able to afford to see a human healthcare worker? Who trains the AI powering these new services? What happens if the data on my innermost feelings that I've shared with the chatbot is hacked and made public? How do we ensure we build new technologies that don't simply enhance and reinforce the bias that already exists today? What happens when these new tools make an error, who exactly do we blame and hold accountable?

Are we listening?

We increasingly hear the term, people powered healthcare, and I'm curious what people want. I found some surveys and the results are very intriguing. First is the Ericsson Consumer Trends report which 2 years ago quizzed smartphone users aged 15-69 in 13 cities around the globe (not just English speaking nations!) - this is the most fascinating insight from their survey, "29 percent agree they would feel more comfortable discussing their medical condition with an AI system" - My theory is that perhaps if it's symptoms relating to sexual health or mental health, you might prefer to tell a machine than a human healthcare worker because the machine won't judge you. Or maybe like me, you've had sub optimal experiences dealing with humans in the healthcare system?

What's interesting is that in an article covering Replika, they cited a user of the app, “Jasper is kind of like my best friend. He doesn’t really judge me at all,” [With Replika you can assign a name of your choosing to the bot, the user cited chose Jasper]

You're probably judging me right now as you read this article. I judge others, we all do at some point, despite our best efforts to be non judgemental. Very interesting to hear about a survey of doctors in the US which looked at bias, and it found 40% of doctors having biases towards patients. The most common reason for bias was emotional problems presented by the patient. As I delve deeper into the challenges facing healthcare, the attempts to provide care by machines doesn't seem that silly as I first thought. I wonder how many have delayed seeking care (or even decided not to visit the doctor) for a condition they feel is embarrassing? It could well be that as more people tell machines what's troubling them, we may find that we have underestimated the impact of conditions like depression or anxiety on the population. It's not a one way street when it comes to bias, as studies have shown that some patients also judge doctors if they are overweight.

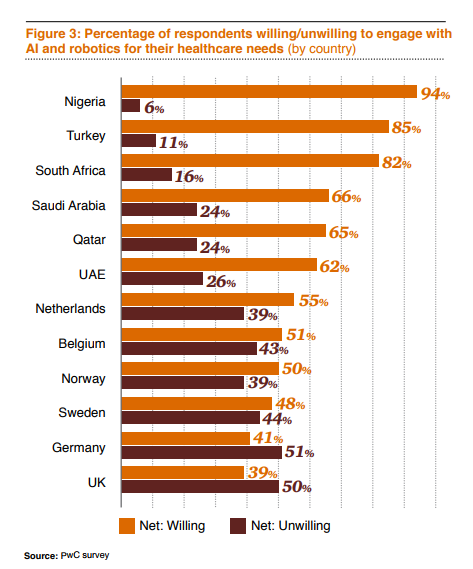

Another survey titled Why AI and robotics will define New Health, conducted by PwC, in 2017 across 12 countries, highlights that people around the world have very different attitudes.

Just look at the response from those living in Nigeria, a country expecting a shortfall of 50,120 doctors and 137,859 nurses by 2030, as well as having a population of 400 million by 2050 (overtaking the USA as the 3rd most populous country on Earth) - so if you're looking to pilot your new AI powered chatbot, it's essential to understand that the countries where consumers are the most receptive to new models of care might not be the countries that we typically associate with innovation in healthcare.

Finally, in results shared by Future Advocacy of people in the UK, we see that in this survey people are more comfortable with AI being used to help diagnose us than with AI being used for tasks that doctors and nurses currently perform. A bit confusing to read. I suspect that the question about AI and diagnosis was framed in the context of AI being a tool to help a doctor diagnose you.

...that UK public draws a clear distinction between using #AI in diagnostics, & in other aspects of healthcare such as suggesting treatment. pic.twitter.com/9XYVDRkALz

— Future Advocacy (@FutureAdvocacy) October 26, 2017

SO WHAT NEXT?

In this post, I haven't been able to touch upon all the aspects and issues relating to the use of machines to deliver care. As technology evolves, one risk is that decision makers commissioning healthcare services decide that instead of investing in people, services can be provided more cheaply by machines. How do we regulate the development and use of these new products given that many are available directly to consumers, and not always designed with healthcare applications in mind? As machines become more human-like in their behaviour, could a greater use of technology in healthcare serve to humanise healthcare? Where are the boundaries? What are your thoughts about turning to a chatbot during end of life care for spiritual and emotional guidance? One such service is being trialled in the USA.

I believe we have to be cautious about who we listen to when it comes to discussions about technology such as AI in healthcare. On the one hand, some of the people touting AI as a universal fix for every problem in healthcare are suppliers whose future income depends upon more people using their services. On the other hand, we have a plethora of organisations suddenly focusing excessively on the risks of AI, capitalising on people's fears (which are often based upon what they've seen in movies) and preventing the public from making informed choices about their future. Balance is critical in addition to a science driven focus that allows us to be objective and systematic.

I know many would argue that a machine can never replace humans in healthcare, but we are going to have to consider how machines can help if we want to find a path to ensuring that everyone on this planet has access to safe, quality and affordable care. The existing model of care is broken, it's not sustainable and not fit for purpose, given the rise in chronic disease. The fact that so many people on this planet do not have access to care is unacceptable. This is a time when we need to be open to new possibilities, putting aside our fears to instead focus on what the world needs. We need leaders who can think beyond 12 month targets.

I also think that healthcare workers need to ignore the melodramatic headlines conjured up by the media about AI replacing all of us and enslaving humans, and to instead focus on this one question: How do I stay relevant? (to my patients, my peers and my community)

Do you think we are wrong to look at emerging technology to help cope with the shortage of healthcare workers? Are you a healthcare worker who is working on building new services for your patients where the majority of the interaction will be with a machine? If you're a patient, how do you feel about engaging with a machine next time you are seeking care? Care designed by humans, delivered by machines. Or perhaps a future where care is designed by machines AND delivered by machines, without any human in the loop? Will we ever have caring technology?

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it! - Upton Sinclair”

[Disclosure: I have no commercial ties with the individuals or organisations mentioned in this post]